Rule Book Russ

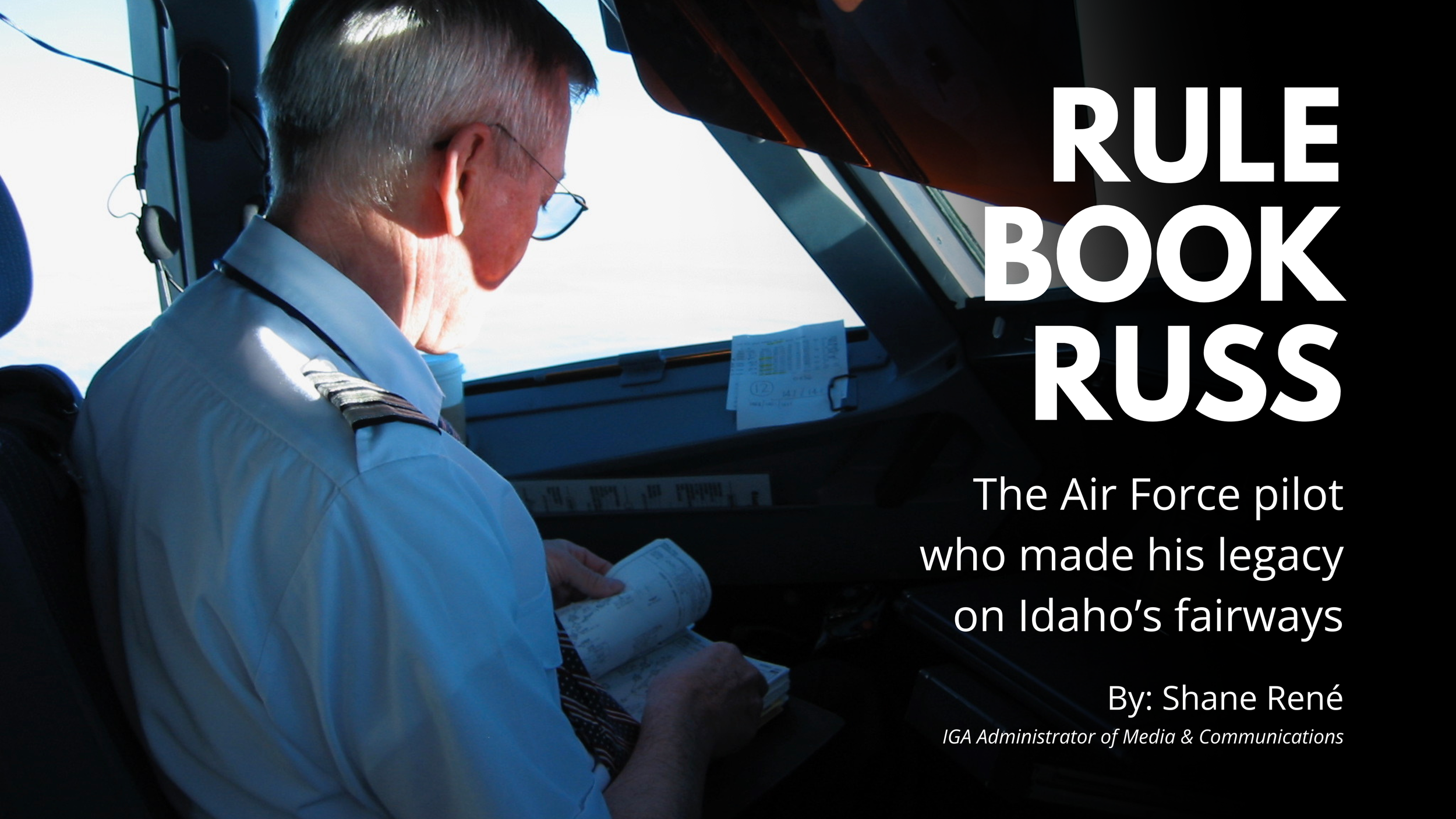

Russ Peterson making preparations for his final flight as a commercial pilot.

For most IGA Championship players, Russ Peterson is the guy who appears when their mood begins to curdle under the high-desert sun. Sprinkler heads. Cart paths. A hole that sorta-kinda looks like it belongs to an animal. No matter where their ball is misbehaving, they pray for relief when Peterson rolls up in a golf cart marked “USGA Rules Official.”

However miffed his judgement may leave them, Peterson is no foe to the championship golfer. He’s not there to catch players cheating or bully them with penalty strokes; he’s there to decode the density of the rule book and set them free on their march to the scoring tent. But Peterson’s judgement extends well beyond the USGA’s Rules of Golf. Wielding a Starbucks peppermint mocha as his gavel, his affection for the policy and procedure embedded in the game has quietly shaped the Idaho Golf Association for nearly two decades.

“If you want to play real golf, you play by the rules,” he said. “Because that’s the game.”

Peterson on a course rating at Pierce Park Greens.

Peterson was introduced to golf in his early teenage years by his great aunt and uncle who shipped him a set of clubs from their home in Pebble Beach. Since his parents didn’t have the means to hire a professional, he taught himself how to grip the club and strike the ball. And when he finally got a chance to play, he received a 140-stroke baptism at Monterey Peninsula Country Club.

“74 on the front, 66 on the back — I can remember it to this day,” he laughed. “And it’s all been downhill since!”

In 2025, Peterson averaged his age — 81.4 — over 157 rounds. His low was 71.

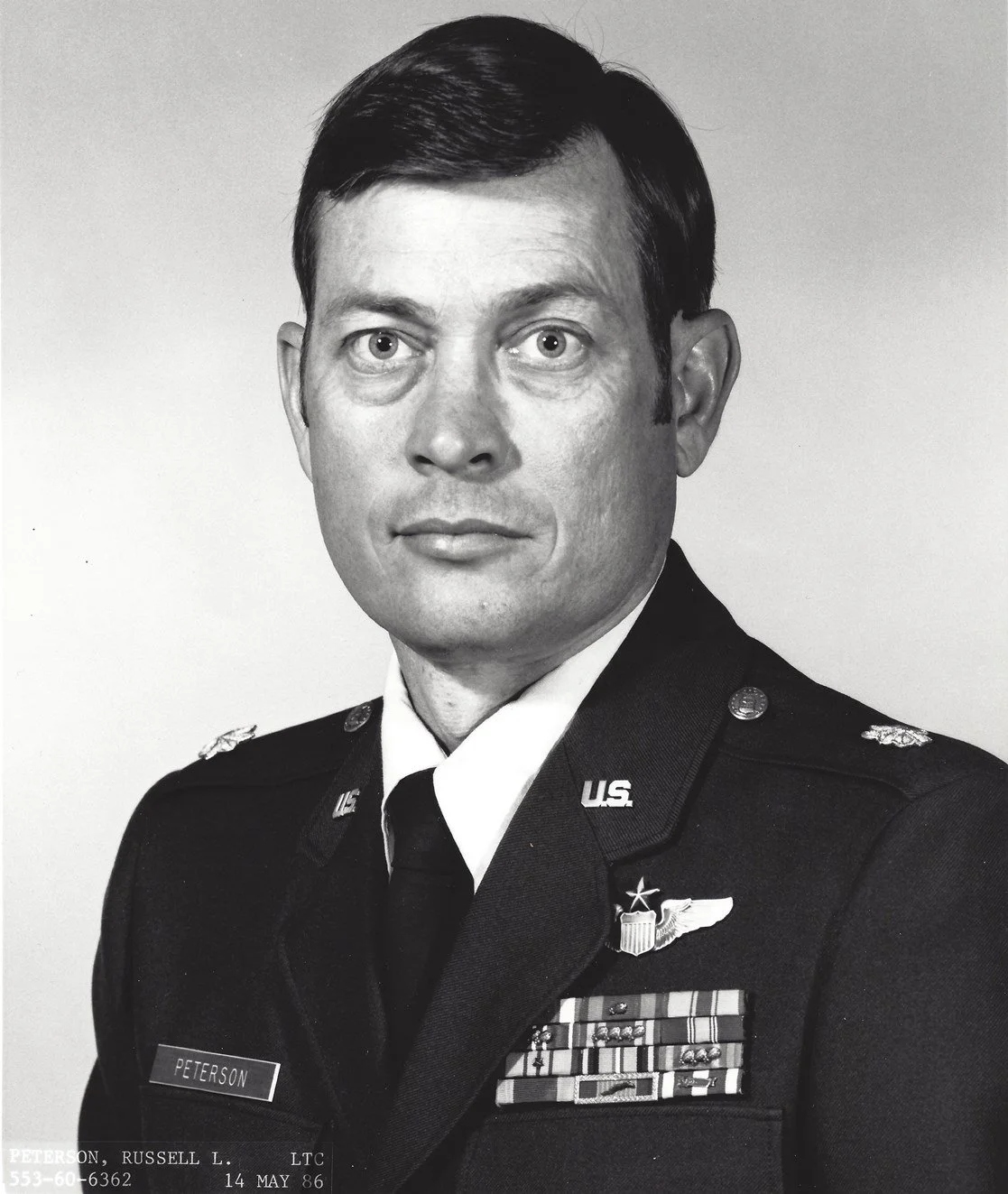

Golf, however, remained a marginal force in Peterson’s early life, instead forging a reverence for rules and regulations high above any golf course. As the Vietnam War raged on, Peterson joined the U.S. Air Force and trained as a navigator. But after just a few years crammed behind the cockpit of a B-52, he went looking for a window seat. He spent the rest of his military career flying KC-135s, an arial refueling plane that underpins our capacity to cloak the world’s airspace.

But over time, golf would grow into a prominent feature of his life on the ground. Peterson first found a cast playing partners when he started teaching at the United States Air Force Academy, which he notes is home to a 36-hole facility featuring an original Robert Trent Jones design.

“And then I went to Grand Forks, North Dakota,” he said. “You don’t play a lot of golf in Grand Forks.”

Peterson would return home to Northern California to round out his military career, teaching new pilots how to fly KC-135s at Castle Air Force Base. Peterson joined nearby Merced Country Club as a non-voting member and established a Handicap Index for the very first time.

Naturally, Peterson retired from the Air Force into regional airlines, signing up with Horizon Air out of Portland. He lived in Vancouver, WA and joined Royal Oaks Country Club. Then he was onto America West (now American Airlines) in Phoenix, where he bought a house at Red Mountain Ranch Country Club.

Peterson in the terminal ahead of his last commercial flight.

Twelve years later, in 2000, Peterson moved to Idaho where his wife, Christine, had family. He joined the IGA and played in a couple of senior events while commuting to Phoenix for work. But in 2004, feeling like he wasn’t ready to retire, he turned 60, aged out of flying, and took a job in the America West training department. (An untimely act of Congress changed the age limit to 65 less than two years later.)

“It’s pretty easy to commute when you’re an active pilot; it’s harder when you’re not an active pilot,” he said. “So, I talked to my wife about moving back to the desert because she hates the desert.”

Mercifully, Peterson sentenced Christine to just a few years back in Arizona. And in that time, he learned how to do Course Rating — the process that underpins the Handicapping infrastructure used by millions of American golfers.

“I always tell Course Rating classes that golf associations have three primary functions,” Peterson said. “They conduct championships, they issue handicaps, and they rate golf courses. And of those three, the pillar is the Rating. Without the Rating, you can’t get Handicaps. Without Handicaps, you can’t get into the championships.”

A natural with numbers, Peterson took quickly to Course Rating. And he found a fitting mentor in Warren Simmons — a fellow retired Air Force pilot and former Air Force Academy golf coach who went on to become the Executive Director of the Colorado Golf Association and chair of the USGA Course Rating Committee. In 2009, the USGA awarded Simmons the Ike Grainger Award for his decades as an expert volunteer.

Peterson was quick to approach the IGA about getting involved with Course Rating when he returned to Idaho in June of 2008. But after his education with a Seal Team of Course Raters in Arizona, what he found in Idaho looked a lot more like the Minute Men — and he was promptly asked to oversee them, relieving a two-man band at the IGA office.

“I asked for a list of the raters, and they said, ‘well, right now it’s just us here in Boise. We’ve got a handful in the Twin Falls area and a couple out of Pocatello,’” he recalled.

Knowing he’d need more soldiers, Peterson set up a Course Rating class. He says 18 to 20 new faces showed up. But at the same time, the USGA was centralizing its Course Rating data, asking its network of associations to audit and transfer their files to Far Hills, NJ — a task that revealed issues far deeper than manpower.

Peterson in 2024 rating Osprey Meadows at Tamarack Resort.

“I spent a good couple of months in the offseason in 2009 just going through [ratings] course by course,” he said. “And I discovered that our Course Rating program was not very good.”

According to his audit, many courses seemed to be rated by just one or two people. USGA procedure requires at least three raters per course. And while teaching a class with more “experienced” raters, he learned that many ratings functioned as little more than a data collection exercise, glossing over steps that give critical context to raw measurements.

Peterson found notable errors at places like Crane Creek Country Club, which climbs through canyons of the North Boise foothills. Rating data falsely indicated that all 18 greens were flat. Headwaters Club (now Bronze Buffalo), which sits at 6,000 feet above the ocean in the Teton Valley, was rated at sea level. Elevation plays a significant role in calculating the effective playing length, which is a core component of all ratings.

Unwilling to abide the status quo, Peterson put together a plan. Over what he hoped would take four or five years, he laid out a schedule to re-rate every golf course in the IGA, no matter where they sat in the seven-year cycle used to keep ratings fresh.

“We were rating 18-22 golf courses every summer for three and a half years,” he said. “Everything needed a fresh look because I saw too many errors when I audited — too many question marks.”

Peterson steered the IGA’s Course Rating program, unpaid, for nearly five years, staying aboard through staff growth and leadership change. His efforts drew a visit from USGA Course Rating guru Scott Hovde, who Peterson says was complimentary about the standard he’s established here in Idaho. At this point, the IGA felt little urgency to hire a full-time staff member to run the newly-reformed department. Eventually, he drew up a contract that got him paid for a few years before the IGA settled on Caleb Cox in 2017.

“Russ was primarily responsible for teaching me how to do Course Rating and how to run a Course Rating department,” current Executive Director Caleb Cox said. “My first impression was: I have no idea who this guy is but he has lots and lots of information — and he’s a little bit scary at first — but he’s incredibly knowledgeable and was incredibly quick to take me under his wing.”

Wings, in fact, are the appropriate analogy for a man who made a legacy on the golf course with principles learned in the air. While flying 737s for America West, Peterson says there was a way of doing things. And much of what Southwest Airlines does is the same; all the things Boeing requires of the airlines that fly their planes (the Rules of Golf). But some of it is different. How the checklist are worded, how many items are on a checklist, and the verbal callouts between pilots during takeoff and landing are examples of what airlines can implement on their own (the Model Local Rules). As a direct result of his involvement — of his knack for negotiating the black and white —The Idaho Golf Association is a fundamentally stronger representative of the rules and regulations that govern our game.

“Sometimes we’re placed in positions for a reason, you know?” he said. “So I’ve always felt like that was one of the reasons I was brought to Idaho.”

In 2026, Peterson will step away from the IGA Board of Directors after nine years of service, during which he served as both President and Vice President. But Peterson is by no means going away. You can be sure to find him out playing The Club at SpurWing on any given day. You can expect to see him at IGA championships and Course Ratings when he’s not on a church mission to Kenya. Even as he wades into his early 80’s, Peterson remains the IGA’s first and most reliable call for anything that begs to be done by the book.

“I told Nicole she’s gonna have to wheel me out to ratings someday,” he said, referring to current Director of Course Rating Nicole Rutledge. Rutledge says she considers Peterson to be something of father figure; someone who taught her the ropes, provides a steady source of support, and falls asleep to Johnny Cash albums as she drives them to ratings in the far reaches of Eastern Idaho.

During his time on the Board of Directors, Peterson played some role in the hire or promotion of seven of the IGA’s eight full-time employees. And they share echoing narratives about their time getting to know him. At first, he’s the hardened military man, rigid on the rules and plain spoken with his perspective. But over time they find themselves, at one point or another, taken by his belly laugh. They’re drawn to an unexpectedly gooey center. Lexie VanAntwerp, the IGA’s Director of Member Services, remembers Peterson paying her a visit after the birth of her son. Director of Junior Golf Cecilia Baney calls him a teddy bear.

“When he saw my wife for the first time after I became ED, he asked her: ‘how does it feel to be the First Lady of golf in Idaho?’” Cox recalled. “The fact that he was thinking about her… looking beyond me at the impact it would have on my entire family… I saw that he was looking deeper than just the job, and rather at the people involved.”

Baney, the IGA’s longest serving employee behind Cox, emphasized just how much Peterson makes IGA staffers feel like more than just an employee. He’s a reminder, she says, that work should never come first. They are husbands and wives, mothers and fathers, sons and daughters — golfers whose lives are defined by so much more. The culture he champions cannot be distilled within the pages of a rule book.

“I take pride in the fact that I had a role in bringing the IGA to where it is today,” Peterson said. “How important that role is — somebody else will have to decide. But I know I had a role in creating the place we are at today.”

Russ Peterson hesitates as he says those words. Being boastful is not his character; but representing the facts of the matter is. And for a man who made his impact with the letter of the law, his legacy is felt a lot closer to the soul.